Africans forced into slavery in America brought with them a diverse range of African polytheistic and Muslim religious traditions. These traditions were often syncretized with one another and with Christianity in America. The diverse American religious traditions that trace their lineage back to the religious traditions of African slaves and African immigrants played an important role in the fight for civil rights in the middle of the 20th century and they continue to inform fights for civil rights and against injustice.

Africans forced into slavery in America brought with them a diverse range of African polytheistic and Muslim religious traditions. These traditions were often syncretized with one another and with Christianity in America. The diverse American religious traditions that trace their lineage back to the religious traditions of African slaves and African immigrants played an important role in the fight for civil rights in the middle of the 20th century and they continue to inform fights for civil rights and against injustice.

View full album

Having established a constitutional framework for political and religious freedom, America still lived with the disquieting lie of its harshest institution: slavery. There had long been vocal critics of slavery, such as the Quaker Anthony Benezet in 1772, who called for an end to the “barbaric traffic” of the slave trade. But on the whole the spirit of “liberty and justice for all” did not extend to the African captives enslaved in America. The first decades of the 19th century brought to a head the deep contradictions between America’s ideals and its practice of slavery.

From the standpoint of America’s ongoing encounter with religious difference, the institution of slavery played a tremendous role in shaping American religious life. It brought African religious traditions—both West African tribal traditions and Islam—to American shores and created a crucible of oppression out of which rose new African American forms of Christian worship and expression. Slavery forced white Americans to rethink their own religious identity, struggling with the deepest dictates of their conscience and the practices of their churches. Many denominations split over the questions raised.

The West Africans brought to North America carried with them a rich variety of African tradition, belief, and practice, but little is documented of the first hundred years of their religious lives here. Their original religious traditions respected the spiritual power of ancestors, and they often worshipped a diverse pantheon of gods overseeing all aspects of daily life: the passage of seasons, the fertility of the natural world, physical and spiritual health, and the success of the community. Their religious life had included initiation rites and naming rituals, folk tales and healing practices, ecstatic dance and song. This religious life clearly took new forms as Africans were separated from one another and from their roots. Many scholars today would argue that the “ring shout” of early black Christian worship is a development of African ecstatic dance traditions, and that the “call-and-response” rhythm of black preaching, hymnody, and gospel music has its roots in the song styles of the West Africans.

With the African slave trade, the first sizable group of Muslims also came to America. While slave trade statistics are fraught with imprecision and the existence of Islam was frequently not recognized by those keeping data, it has been estimated that somewhere between 10% and 30% of the slaves brought to America between 1711 and 1808 were Muslim. They brought their practice of prayer, their fasting and dietary practices, and their knowledge of the Qur’an with them to American shores. Bilalia Fula, for example, was a slave on the Sea Islands of Georgia in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. According to all accounts, Bilalia gave his children Muslim names, wore a fez and long coat, spoke French, English, and Arabic, and was finally buried with his prayer rug and his Qur’an. Other early American Muslims whose accounts have been recorded include Salih Bilali, a slave on St. Simon’s Island, Georgia, and Omar Ibn Said, who left behind an autobiographical narrative.

Thus, in the early years of African slavery, the religious traditions of West Africa, often already blended in a syncretic way with Islam, were no doubt part of the American religious landscape. Slave narratives written by the children or grandchildren of African-born slaves sometimes included recollections of traditional African rituals or Islamic prayers. Eventually, these traditions became intertwined with Christianity as it developed among the slaves. There is a lively scholarly debate today as to whether African religious beliefs and practices really survived the pressures of slavery or, instead, were eradicated as slaves converted to Christianity. Many scholars argue that African traditions changed radically but also persisted as what some have called “Africanisms” in African American religion and culture.

The early white resistance to Christian missionary efforts among the African slaves is well known. White colonists feared that slaves’ conversion would require their owners to emancipate them, that the Africans were too brutish to benefit, or that conversion would inspire insubordination and revolt. Moreover, the scarcity of missionaries affected not only blacks but whites as well. Albert J. Raboteau, considered the leading expert on slave religion, concludes, “During the first 120 years of black slavery in British North America, Christianity made little headway in the slave population.” But with the “Great Awakening” of the 1740s, Methodist and Baptist movements made inroads into the slave population of the South.

For many slaves, Christianity—once adapted to their situation—became a deeply held faith and a means of self-preservation. Slaves often identified themselves with both the people of Israel held captive in Egypt and with the poor and downtrodden to whom Christ promised the greatest rewards in heaven. Both in sermon and song, slaves lifted up these themes of hope, freedom, and justice in their expressions of Christianity. They transformed Christian faith and worship into their own distinctive idiom, and in doing so they made a profound and lasting contribution to the shape of American Christianity and American music.

The deep moral dilemmas provoked by the practice of enslaving Africans also fractured Christian America. Several denominations split over the issue: the Methodists in 1844, the Baptists in 1845, and the Presbyterians in 1857. In the decades between the writing of the Constitution and the onset of the Civil War, these conflicts dominated American religious and political life. Some whites continued to argue in support of slave holding, while others insisted that the importation of slaves must be halted. Going one step further, the abolitionists fought for the total and immediate emancipation of the slaves.

Both sides appealed to religion. Defenders of slavery accused abolitionists such as William Ellery Channing, William Lloyd Garrison and Elijah Lovejoy of being religious and political radicals over-influenced by Thomas Jefferson and the European Deists, who were portrayed as un-Christian seekers of the “Abolition of God.” Free black abolitionists cried out against the hypocrisy of so-called Christian slaveholders. David Walker, son of a slave father and a free mother, wrote an “Appeal” in 1829 declaring God’s wrath and judgment on a country which allowed slavery to continue. Frederick Douglass charged that “the church and the slave prison stand next to each other… The church-going bell and the auctioneer’s bell chime in with each other; the pulpit and the auctioneer’s block stand in the same neighborhood.”

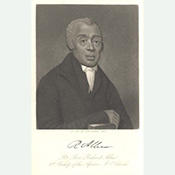

By this time, there were already two predominantly black denominations. Richard Allen, a former slave, had left his Philadelphia church and founded the Bethel Church in 1794. He had previously been a member of a predominantly white Methodist church but was one day assaulted for praying in a part of the church where blacks were not allowed. The church he founded became the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) denomination in 1816. Jarena Lee, one of America’s first women to preach the Gospel, got her start in Richard Allen’s Philadelphia church. The AME Zion denomination began in New York in 1821, when a group seceded from a mixed-race church in which blacks could take the sacrament of communion only after all the whites had been served.

The issues that challenged American Christianity in the 19th century resurfaced in a different form in the 1950s and 1960s, when the struggle for the civil rights of African Americans once again fractured Christian churches. In this period, the liberal religious realignment of those opposing racism included both black and white churches, and both Christians and Jews.

The relation of America’s racial diversity to its religious diversity is a complex and ongoing story. The primary actors in this story have been African Americans who have struggled for racial justice for generations. But the issues raised in this struggle have been of utmost consequence for people of all races and religions coming to America. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Chinese Buddhist railroad workers, Sikh lumbermen, Syrian Muslim pack peddlers, and Japanese Buddhist farmworkers all faced prejudice and discrimination—articulated variously in racial, religious, and economic terms.