Daoism

Daoism

Daoism

Daoism Timeline

Daoism in the World (text)

2698 - 2598 BCE The Yellow Emperor

Gongsun Xuanyuan, also known as Huangdi or Yellow Emperor, is regarded as the first emperor and leader of China, and is said to have lived during this period. He is also a god in Chinese folk religion. The Yellow Emperor is often associated with the origin of the Dao, as some scholars trace elements of Daoism to folk traditions in prehistoric China.

C. 6th Century BCE The Life of Laozi

Laozi was a scholar and philosopher who is said to have lived during the Warring States Period, a period of conflict in China. Like his contemporary, Confucius, Laozi developed a response to the socio-political turmoil in China. But unlike Confucius, who focused on governmental and societal virtues like ren (humaneness), Laozi emphasized wu-wei (flow, effortless action, simplicity), meaning “letting things happen on their own,” and cultivation of sanbao (compassion, humility, and frugality). He believed in the harmony of all things and the importance of concern for others, and was dismayed at the corruption he saw in government and the pain it produced. Laozi attracted many students and disciples, teaching that people could have more fulfilling existences by moving with the natural flow of the Dao, or “the Way” - the natural process of the Universe.

C. 6th Century BCE Daodejing

Although the exact date of the recording and compilation of the Daodejing, or Tao Te Ching, is disputed, Daoist tradition attributes its authorship to Laozi who was asked to write down his wisdom on his way out of civilization. The Daodejing contains the foundational principles of the Dao (the Way), and became the basis for the continuation of Daoism as a tradition, religion, and philosophy.

369 - 286 BCE Zhuangzi and the Zhuangzi

The second most important teacher in the Daoist tradition is Zhuangzi, who further developed Daoism. He is attributed with the Zhuangzi, a compilation of his writings on Daoist teachings, which is one of the two foundational texts of Daoism (along with the Daodejing). While the Daodejing is addressed to rulers, the Zhuangzi provides guidance for private life.

142 CE Way of the Five Pecks of Rice

Zhang Daoling founded the Way of the Five Pecks of Rice, or The Celestial Masters, a Daoist movement emphasizing attainment of balance in qi. This was the first organized form of Daoism, and later developed into the Celestial Masters (Tianshi dao) which was formally recognized by the state in 215 CE. The movement led to Daoism becoming a distinct tradition that persists today, comprising rituals, priesthood, and a universalist message -- in contrast to the prior form of Daoism which was principally philosophical. Around this time, Laozi was recognized as a deity by the state.

C. 2nd-6th centuries CE New Daoist Communities and Practices Spread

New Daoist communities, movements, and ways of physical and spiritual cultivation developed and spread throughout the first half of the first millennium CE. For example, the practice of Daoist alchemy further developed during this period, especially among many Chinese women.

184 CE The Yellow Turban Rebellion

The Yellow Turban Rebellion was a peasant revolt against the ruling Han Dynasty in China that broke out in 184 CE in response to political discontent and famine. It was led by Zhang Jue, the founder of an esoteric school of Daoism, with fellow rebels (wearing yellow scarves on their heads) from various Daoist sects. Though the movement was suppressed by the Han, the rebellion inspired later uprisings associated with Daoism.

C. 226 CE Wang Bi and Daoist Compatibility

Wang Bi, a Chinese philosopher, integrated Daoist ideas into Confucian education. His advancement of the compatibility of Daoism with Confucian and Buddhist thought ensured that Daoism remained a core part of Chinese culture.

252 - 334 CE Wei Huacun and The Shangqing School

Wei Huacun, a female Daoist religious leader, founded the Shangqing School of Daoism, also known as the Way of Highest Clarity. From immortals she received revelations of Daoist scriptures that became the foundation for the Shangqing School. Tao Hongjing (456 - 536 CE) later compiled the canon, thought, and practice of the Shangqing School. Many of its practices survive into the 21st century CE.

C. 4th Century CE The Lingbao School of Daoism

Around the 4th/5th century CE, The Five Talismans (Wufujing) were written by Ge Chaofu based on earlier alchemical works by Ge Hong. These texts formed the basis for the Lingbao School of Daoism, or the Way of Numinous Treasure. The School developed its own pantheon of gods, views of reincarnation, and collective rituals distinct from other Daoist schools. It interpreted Daoist thought and practices in ways generative for not only individual but also universal salvation. Lingbao rituals continue to be an important part of Daoist practice today.

618 CE Green Goat Palace Temple Built

The Qingyang Gong Shi (Green Goat Palace Temple) was built in the early Tang Dynasty at the supposed birthplace of Laozi, and the site where he is said to have given his first sermon. The Temple is the oldest and largest Daoist temple in southwest China.

618 CE - 906 CE The Tang Dynasty and Imperial Daoism

During the Tang Dynasty, Daoism became the official religion of the state and was fully integrated in the imperial court system. The state subsequently mandated that people keep Daoist writings in their home. (However, for many Chinese people, Daoism was equally integrated with other traditions and schools of thought, especially Confucianism and Buddhism.) The end of the Tang Dynasty signaled the end of the classical period of Daoism, which witnessed a flourishing of schools and practice.

7th century CE Daoist Missionaries to Korean Peninsula

The Tang Dynasty sent Daoist missionaries to the Korean peninsula, establishing the first Daoist roots there.

712 CE Civil Service Examinations Feature Questions about Daoist Texts

Under the rule of Daoist Emperor Xuanzong, imperial civil service examinations began to feature questions about Daoist texts.

960 - 1279 CE The Song Dynasty

Many Song emperors actively promoted Daoism and helped to propagate Daoist texts. Throughout the dynasty, there was increasing interaction between the elite, organized Daoist communities and the local, folk traditions of Daoism with non-ordained ritualists. These interactions led to many local deities being integrated into the bureaucracy’s Daoist pantheon.

This period also saw the emergence of new forms of Daoist ritual and thought, especially as Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism were integrated through the Neo-Confucian school. Under the Song Dynasty, Quanzhen (Perfect Truth) Daoism and Zhengyi (Orthodox Unity) Daoism were developed; these are two major sects of Daoism that persist today.

1112 CE - 1170 CE Wang Zhe and the Quanzhen School

During the early Jin dynasty (1115-1234), Wang Zhe founded the Quanzhen School, or Way of Complete Perfection. This school espoused a monastic version of Daoism, emphasizing breathing and meditation as a way to attain balance of qi. It also aimed to harmonize the three teachings -- Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism -- and heavily influenced the Mongol Yuan dynasty. The Quanzhen School is a major school of Daoism existing today.

1281 CE The Yuan Debates

The Yuan Debates, a number of exchanges occurring between Buddhists and Daoists during the Yuan Dynasty, led to a government-sponsored burning of Daoist texts in 1281 CE. While devastating, this event also created an opportunity for a renewal of Daoism, and the Celestial Masters sect regained preeminence by the end of the Yuan Dynasty.

1445 CE The Ming Canon

The Ming Canon of 1445, also known as Zhengtong Daozang (Daoist Canon of the Zhengtong Reign Period), was compiled during a time of flourishing for Daoism in the Ming Period (1368 CE - 1644 CE). The compilation includes around 1500 commentaries on the two foundational Daoist sources - Daodejing and Zhuangzi - by various Daoist masters. The Ming Canon includes three main sections on meditation, ritual, and exorcism, known as the Three Grottoes.

1644 CE - 1911 CE Daoism in the Qing Dynasty

Throughout this period, new movements within Daoism emerged, despite many restrictions on Daoist literature, ritual, and leadership during the Qing dynasty. As Daoism became more influenced by popular religious culture and practices, there was an upsurge in the production of Daoist texts on ethics and morality, and Daoist arts like Taiji (Tai Chi) and Qigong became increasingly popular.

1919 CE The May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement, beginning in 1919, was an anti-imperialist cultural and political movement that sought to bring about modernization and westernization in China. The movement targeted and rejected traditional religions of China, such as Daoism and Confucianism, as antithetical to progress and modernization.

Mid-1900s CE Study of Daoism in the West

Throughout the 20th century, Daoism grew as a field of study in the West; Prof. Henri Maspero in Paris was one of its largest proponents. Later in the 20th century, American Michael Saso became the first westerner to be initiated as a Daoist Priest.

1966 CE - 1976 CE The Cultural Revolution in China

Mao Zedong came to power in China in 1949 and established the People’s Republic of China. In 1966, he launched the Cultural Revolution, which aimed to eradicate traditional elements of Chinese culture -- especially traditional religions such as Daoism. Many Daoist temples were destroyed, and Daoist practices were outlawed.

1980 CE to Present — The Revival and the Future of Daoism

Since the death of Mao in 1976, the Chinese government has been more tolerant toward traditional religions of China. The practice of Daoism is once again permitted and is undergoing a revival as a new generation of Daoists aim to recover their tradition and rebuild their temples and monasteries. Daoism has also spread to Europe and North America, where many Daoist organizations have been established. Practices like Taiji (Tai Chi) and Qigong have seen considerable interest in the West and are continually being adapted to Western contexts.

Selected Publications & Links

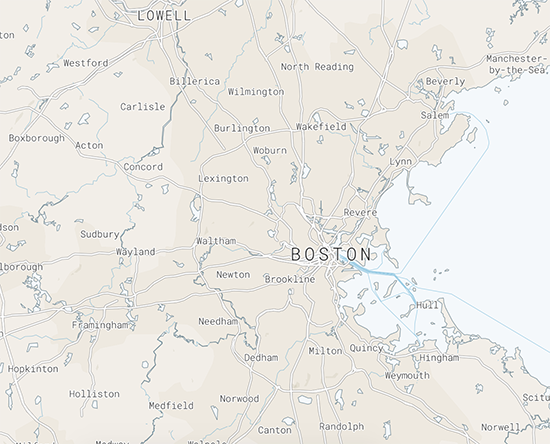

Explore Daoism in Greater Boston

Though there are significant Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Korean immigrant communities in Greater Boston, East Asian traditions such as Confucianism, Daoism, and Shintō are difficult to survey as there are very few religious centers. These traditions are deeply imbedded in the unique history, geography, and culture of their native countries and are often practiced in forms that are not limited to institutional or communal settings.