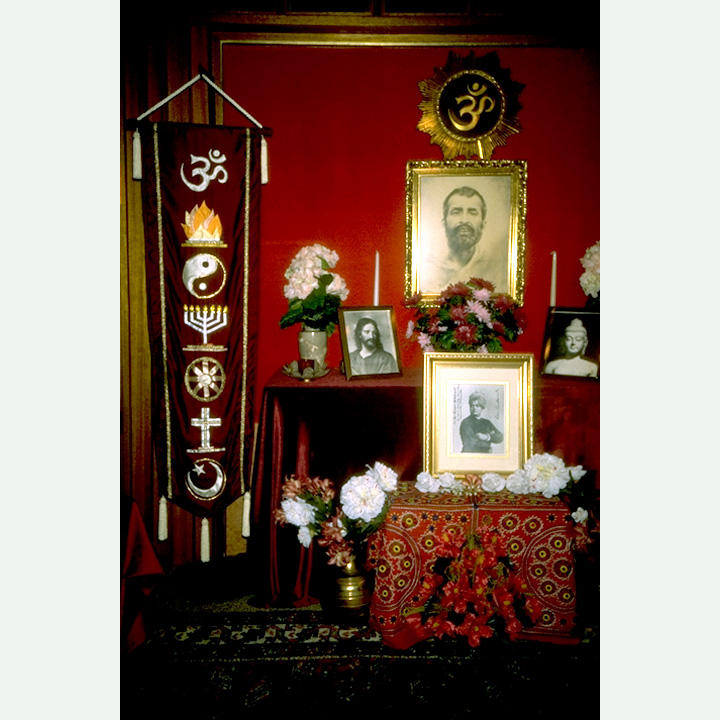

“The one and the many” reflects the Hindu philosophy of India as well as the exchanges between India and the West. Hindu practices influence and are influenced by other religious traditions in India; the diversity of different religions continue to create dynamic patterns of interrelation.

“The one and the many” reflects the Hindu philosophy of India as well as the exchanges between India and the West. Hindu practices influence and are influenced by other religious traditions in India; the diversity of different religions continue to create dynamic patterns of interrelation.

View full album

Throughout its long history, the Hindu tradition has shared common soil with other religious traditions. India is the homeland of Buddhism, which flourished in India for over 1,500 years from the time of the Buddha in the 6th century BCE until about the 11th century. The Jain tradition of monks, nuns, and laity, which began about the same time as the Buddhist tradition, continues to flourish in India today. The Christian tradition also has ancient roots in India, where Christians trace their origins back to the Apostle Thomas in the 1st century. The Jews have an old community started by traders in the southern state of Kerala and in Bombay. The Parsis are followers of the Zoroastrian tradition with roots in what is now Iran.

Beginning in the 11th century, the Muslim tradition took root in India and developed a distinctive Indo-Muslim culture. Before the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, about one third of all Indians were Muslims, and even now about 13 percent are Muslims. Finally, the Sikh tradition began in northwest India in the 16th century with the teaching of Guru Nanak and has evolved into a vibrant and distinctive religious community. With the British Empire, beginning in the late 17th century, came Protestant Christianity and the mission movement. As commerce developed between India and the West, currents of intellectual and religious thought traveled back and forth as well.

Some Hindus today insist that the whole multi-religious context of India is basically “Hindu.” By this they might mean a tolerant cultural milieu, defined not by a creed, but by a broad ethos or world view. They would argue that, on the whole, the Hindu world view has been one of harmony, not conflict. This Hindu milieu has absorbed many a people and tradition, repeatedly affirming the integral oneness of Reality and the multiple perceptions of that same Reality. While Muslim, Sikh, and Christian communities have distinguished themselves from this broad contextual “Hindu” background, they have nonetheless been influenced by it.

In this broad perspective, the theme of the One and the many is a constant, like a continuously evolving raga, a musical scale with a multitude of variations. No culture on earth has developed as complex an understanding of human and divine “manyness.” The Hindu “solution” to diversity, however, has never been that of the melting pot. It is, rather, that of the kaleidoscope in which the distinct pieces continually fall into patterned wholes, over and over, with each twist of the wrist. Diversity is preserved and valued in a flexible and dynamic pattern of interrelation.

So one might say that pluralism is one of the foundational contributions of the Hindu perspective. Difference, in this view, is not a threat to oneness, but constitutive of oneness. The whole is made up of difference, its many parts not isolated but in interrelation. To say “this is the one and only” may be a marker of importance to other cultures. Hindu India, however, has long taken a different measure of the meaning of plurality.

However, this past century has also seen the emergence of a Hindu perspective that is itself more narrowly defined, that is more exclusive than pluralist. This is sometimes referred to as "Hindu nationalism," defining Hindu India in political and ideological terms to exclude those they deem to be outsiders, largely Muslims. The political parties and paramilitary groups that press this view rally around issues such as rebuilding a Hindu temple at the site said to be the birthplace of Lord Rama or banning cow slaughter and beef eating. The rise of this perspective into state and national elective politics has begun to reshape the meaning of "Hindu" for many in India.