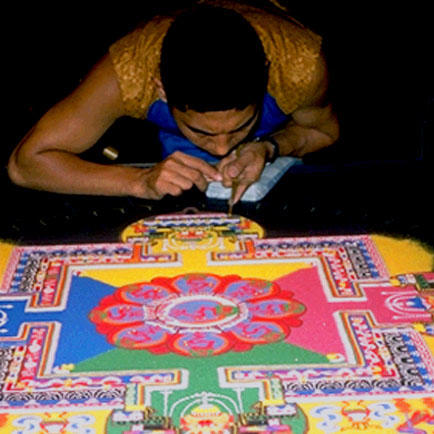

In Vajrayana Buddhism, the mandala (“circle”) serves as a diagram of the cosmos. Creating a sand mandala can take weeks and requires intense concentration, but the ritual practice requires the mandala be destroyed or dismantled after its completion. This emphasizes the impermanence of all created things.

In Vajrayana Buddhism, the mandala (“circle”) serves as a diagram of the cosmos. Creating a sand mandala can take weeks and requires intense concentration, but the ritual practice requires the mandala be destroyed or dismantled after its completion. This emphasizes the impermanence of all created things.

View full album

The word mandala, originally a Sanskrit word, means simply a “circle” and, by extension, a “world.” In the Hindu and Buddhist traditions, mandalas are also symbolic circles that represent the entire world in a microcosm. The Tibetan term for mandala, kyinkor, means “center and surrounding environment.” The center with its surrounding geometric designs, its doors, its guardians, and its gods—all become charged with the order and the energy of the whole cosmos. Visualizing the world created in the mandala with all its color and detail becomes a powerful and finely tuned meditation practice.

Creating a mandala to serve as a focus of ritual and meditation has become a highly elaborate process in the Tibetan Vajrayana tradition. The mandala may be painted on cloth, created of colored particles of sand, or visualized in the mind’s eye. In the United States, thousands of people who would not otherwise have seen this process have had a chance to observe Tibetan monks creating a mandala in museum installations or on university campuses. For instance, the Kalachakra Mandala, the “Wheel of Time,” has been painstakingly created over a period of several weeks in the American Museum of Natural History in New York, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the I.B.M. Gallery in New York.

The mandala is created of fine multi-colored sand, placed grain by grain in the intricate circle. Working outward from the center along a pattern that has been laid out, monks place the grains using special metal funnels that release a steady stream of sand, one grain at a time. The meditation does not begin on completion of the mandala; rather, the creation of the mandala is itself a form of meditation for the Namgyal monks of the lineage of the Dalai Lama. The placing of the sand requires the finely honed quality of attentive, unwavering presence that is meditation. The mandalas, some six feet in diameter, take three to four weeks to complete. In the United States these sand mandalas have been dedicated to peace—both inner and universal peace—the peace that requires the balance and wholeness that the mandala embodies.

The world created here becomes the symbolic abode of the deity, in this case the Kalachakra deity and 822 aspects of Kalachakra represented in the mandala. They are situated at every point in the pattern of concentric circles and squares that radiate from the center. There are the cardinal directions with their respective colors and guardians. There are the layers that compose the human person—circles representing the body, speech, mind, and, at the center, pure bliss, pure wisdom. The elements of the universe are laid out—earth, water, fire, wind, space, and, finally, consciousness. The whole interlocking world of life and death, buddhas and bodhisattvas, is present in this Wheel of Time.

The same process is undertaken when the mandala is created for a ritual, such as the Kalachakra initiations, which have taken place several times in the United States, including the huge Kalachakra initiation conducted by the Dalai Lama in Madison Square Garden in New York, in 1992. Many monks work intensively to create the sand mandala, completing the whole in only three days. When it is completed, the ritual master, in this case the Dalai Lama himself, invites the deities to come from their celestial abode and reside in the mandala. Kalachakra and the other deities become present for the period of the Kalachakra initiation. Initiates are introduced to them by the ritual master and are guided through the aspects of the mandala. When the ritual is completed, the deities are requested to return again to their celestial abode.

Whether in the museum or in the ritual arena, the sand mandala is not permanent. After being on display or after serving as divine residence during the ritual, the mandala is dismantled. The intricate sand painting is ritually swept away. The multi-colored sand is poured together in a large container and brought to San Francisco Bay or the East River to be ritually deposited. The impermanence of all created things is enacted here in the painstaking creation of an intricate, exquisite work of art—and its destruction. A symbolic world comes into being, grain by grain, and passes away.