For most of its history, Judaism has traditionally been a patriarchal religion; however, women’s movements since the mid-20th century have advocated for and achieved greater equality for women in many Jewish denominations. Jewish women are now ordained as rabbis in all non-Orthodox denominations, and many Jewish theologians are expanding their field of interest to include the roles and characters of biblical and historical Jewish women.

For most of its history, Judaism has traditionally been a patriarchal religion; however, women’s movements since the mid-20th century have advocated for and achieved greater equality for women in many Jewish denominations. Jewish women are now ordained as rabbis in all non-Orthodox denominations, and many Jewish theologians are expanding their field of interest to include the roles and characters of biblical and historical Jewish women.

View full album

One of the greatest challenges to Judaism in America has been the advent of the women’s movement. For most of its history, Judaism was a patriarchal religious tradition, relegating women to a lower status than men. The traditional domain of women in Jewish life was the home, which—despite the protests of apologists—was not a religious institution with communal influence. Although women were responsible for preparing food, for example, it was the male rabbi who regulated the practice of kashrut, the Jewish dietary laws. Religious activities that took place in the public sphere outside the home, such as study, prayer, and acts of loving-kindness, were considered mandatory only for men. Women occupied a subsidiary space in the Jewish house of prayer and were scarcely admitted to the study house at all. While the Reform movement of the 19th century adopted some measures intended to equalize the role of women in the synagogue, not until the 1970s did the structure of Judaism begin to change in response to the feminist critique.

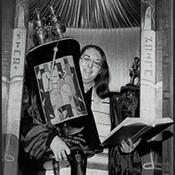

Once the feminist revolution burst on the scene in the 1960s, it was only a matter of time before women’s rising consciousness of social and economic inequities would extend to religious communities as well. As in many American Protestant denominations, the liberal movements of American Judaism soon began to contemplate fully including women by voting to train and ordain women for religious leadership as rabbis. From its founding in 1968, the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College opened its doors to women and graduated Rabbi Sandy Eisenberg Sasso in 1973. And one year earlier, the Reform seminary Hebrew Union College had made the decision to ordain women, promptly giving its own student, Sally Priesand, the distinction of becoming the first woman rabbi in America. The Conservative movement did not sanction women’s ordination until 1983, with the first Conservative woman rabbi, Amy Eilberg, graduating two years later. But the issue remains controversial within Conservative Judaism, and has deepened the divide between Orthodoxy—which rejects women rabbis—and the other Jewish movements.

Feminism began to reshape American Judaism beyond the issue of women rabbis. In 1972 the New York-based Jewish feminist group Ezrat Nashim issued “Jewish Women Call for Change,” a manifesto demanding the equalization of religious rights for women in Conservative Judaism. Their name has a double meaning, referring to the traditional separate seating for women in the synagogue and yet meaning, literally, “the help of women.” For the next two decades, Jewish women began to demand and receive equal status in both synagogue worship and governance. As more women rabbis and cantors serve as role models, it has become commonplace for women to accept all the religious responsibilities and to enjoy all the religious benefits that were formerly the domain of men.

More recently, the egalitarian emphasis has been replaced by a “feminization” of contemporary Judaism. Reclaiming aspects of traditional Judaism which relate to the female experience, many have begun to introduce new rituals and perspectives into the Jewish canon. Jewish history is being rewritten to include women’s experiences, as in the unique prayers for women called techinot. In a modern version of Midrash, Jewish texts are being reinterpreted to uncover the woman’s point of view. Jewish theology is being rethought, and God is being reconceived. Theologian Judith Plaskow’s now classic book Standing Again at Sinai (1991) revisits the major themes of Torah, God, and Israel, reshaping the meanings of Jewish community and theology from a feminist perspective. Meanwhile, new prayers have been composed to reflect the experience of Jewish womanhood, such as in the volumes by poet Marcia Falk. Women’s prayer and study groups have sprung up, many meeting around Rosh Chodesh, the first of the lunar month, an occasion to observe the new moon and celebrate women’s bodily cycles.

But women’s long overdue participation in the Jewish mainstream has had the greatest impact. Due largely to their influence, the key issues of Jewish life today tend to be family, education, community, healing, and spirituality. While the renewed importance of these may be attributed to other factors as well—and while all are actively promoted by men too—it is nonetheless apparent that this opening of the religious sphere has not only changed the lives of Jewish women, but has also begun to change Judaism. While this is still a controversial development in some Jewish circles, most American Jews see this as a welcome trend that will no doubt continue in the years to come.