In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many Jews emigrated from the Pale of Settlement, a large Polish and Russian territory in which Jews were allowed to live in impoverished shtetls (small Jewish villages). Most immigrant Jews from these areas had not cultivated the same religious reforms as the Jews of Germany and Western Europe. As a result, these new Jewish immigrants to America developed a more traditional movement called Orthodox Judaism.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many Jews emigrated from the Pale of Settlement, a large Polish and Russian territory in which Jews were allowed to live in impoverished shtetls (small Jewish villages). Most immigrant Jews from these areas had not cultivated the same religious reforms as the Jews of Germany and Western Europe. As a result, these new Jewish immigrants to America developed a more traditional movement called Orthodox Judaism.

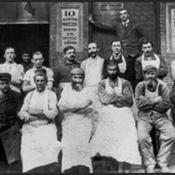

Between 1881 and 1914, more than two million Jews from Eastern Europe immigrated to the United States, transforming the landscape of American Judaism yet again. Whereas the Jews of Western Europe and America had undergone a process of religious modernization for decades, the Jews of Russia and Poland had not. Sheltered from the modern world, they lived in the Pale of Settlement, a large territory stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea, created by the Czars as a separate Jewish enclave. In that region, traditional Eastern European Jewish culture had been maintained through the media of the Jewish religious tradition, the Yiddish language, and the intensive social life of an all-Jewish environment called the shtetl. Hasidic mysticism and the modern Zionist and Bundist movements all gained followers in shtetls. Following the 1881 assassination of Czar Nicholas and the subsequent pogroms against the shtetl populations, a wave of Jewish emigration ensued, and many Eastern European Jews sought refuge in America. This immigration period would transform the fabric of Jewish peoplehood in America to something altogether new.

Little affected by the Enlightenment and Emancipation of the West, Eastern European Jews coming to America brought with them a traditionalist notion of Judaism. Though many would lose some elements of this traditionalism as they settled in America, even those who dropped all outward forms of religious observance retained an inward sense that the only authentic Judaism was the tradition of Torah and mitzvot. This would come to be known as Orthodox Judaism, the word “Orthodox” being a term coined to describe their reaction against Reform. The development of Orthodox Judaism in America was a conscious attempt to offset what were perceived to be the debilitating effects of a secular society, a Christian environment, and Reform Judaism. Indeed, there were some rabbis and other traditional Jews who eschewed the lure of America altogether, for fear that it was a treyfa medina, or “an unkosher land.”

The transplanting of Eastern European Orthodoxy in America began with the swift establishment of a supplementary school, the Machzike Talmud Torah—“The Ones Who Hold Strong to the Teaching of Torah”— in 1883, alongside a full-time religious school, Yeshivat Etz Chaim, in 1886. Both were located on the New York City’s Lower East Side. In 1887, Rabbi Moses Weinberger published Jews and Judaism in New York, a biting critique of what he considered to be an anarchic American Judaism. Later that year the newly formed Association of American Orthodox Hebrew Congregations decided to import religious authority in the person of Rabbi Jacob Joseph (1848-1902) from the city of Vilna, in Poland. Arriving in July, 1888, the new chief rabbi of America was greeted with excitement, but his attempt to establish a European-style Orthodoxy with a chief rabbinate was doomed to initial failure. Only decades later was Old World Judaism re-established on American soil, with the influx of entire communities of ultra-Orthodox Jews just prior to and after World War II. Today, various Hasidic sects and other “black hat” communities, as they came to be called, flourish in Brooklyn, New York and elsewhere in America.