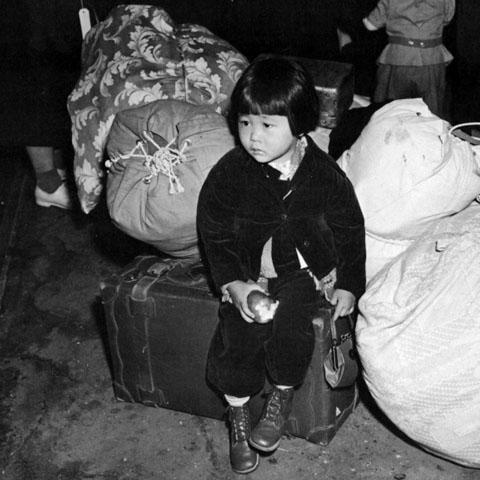

After the outbreak of the Pacific War between the United States and Japan in 1941, Japanese Americans who had already put down roots in America—citizens and noncitizens alike—were sent to internment camps. The internment crisis lasted from 1942 until 1946 and fundamentally reshaped Japanese Buddhist institutions, such as the Buddhist Churches of America, which afterward attempted to “Protestantize” Buddhist temples and organizations.

After the outbreak of the Pacific War between the United States and Japan in 1941, Japanese Americans who had already put down roots in America—citizens and noncitizens alike—were sent to internment camps. The internment crisis lasted from 1942 until 1946 and fundamentally reshaped Japanese Buddhist institutions, such as the Buddhist Churches of America, which afterward attempted to “Protestantize” Buddhist temples and organizations.

View full album

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Chinese and Japanese communities that remained in the United States put down roots. Their religious institutions were modest and included Chinese, Japanese Jodo Shinshu, and a few Soto and Rinzai Zen temples. By far the largest was the Jodo Shinshu, called the Buddhist Mission of North America, which had 123 ministers in 1930.

After the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, however, the Japanese American community came under severe attack. Buddhist priests and other community leaders were singled out for immediate arrest because they were thought to be particularly prone to disloyalty toward the United States. All Japanese Americans on the West Coast, citizens and noncitizens alike, were ordered into internment camps for the duration of the war.

In the camps, Buddhist priests served as community leaders, and Buddhist services continued in a nonsectarian form. The experience of internment made a lasting impression in the Japanese American Buddhist community in two ways. First, because loyalty to America was often tied to being Christian rather than Buddhist, the membership of many temples declined after the war. Second, for the Buddhist organizations that remained viable—such as the newly renamed Jodo Shinshu organization, Buddhist Churches of America—there began a process of the “Protestantization” of its liturgical and institutional forms. The pews and hymnbooks, organs and responsive readings of the Jodo Shinshu temples began to conform to the look and feel of a Protestant church.