Living in luxury, the young Prince Siddhartha traveled outside his palace and encountered the Four Sights: an old person, a sick person, a dead person, and a wandering ascetic. He left his royal life to live in the forest, and he began his training in meditation and asceticism in hopes of discovering the root of human suffering. Rejecting the luxury of the palace and the self-denial of the forest-dwelling ascetics, he chose to pursue a "middle way" between the two extremes.

Living in luxury, the young Prince Siddhartha traveled outside his palace and encountered the Four Sights: an old person, a sick person, a dead person, and a wandering ascetic. He left his royal life to live in the forest, and he began his training in meditation and asceticism in hopes of discovering the root of human suffering. Rejecting the luxury of the palace and the self-denial of the forest-dwelling ascetics, he chose to pursue a "middle way" between the two extremes.

View full album

What we know about the life of the historical Buddha can be sketched from legends. One of the most beautiful literary renderings of the story is told by Ashvaghosha in the 1st century CE. Prince Siddhartha Gautama is said to have been born in the royal Shakya family in a place called Lumbini, which is located in present-day Nepal, at the foothills of the Himalayas. There is some debate over the date of his birth, with some citing it at taking place in 563 BCE and others citing 480 BCE. At the time of his birth, seers foretold that he would either become a great king or an enlightened teacher. If the prince were to see the “four passing sights”—old age, sickness, death, and a wandering ascetic—he would renounce his royal life and seek enlightenment.

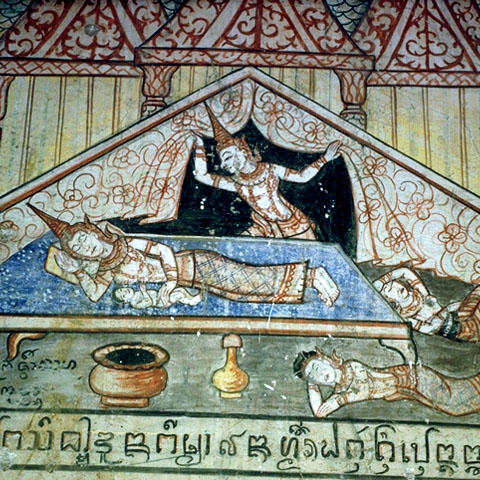

His father, the king, was determined that his son become a great ruler and tried to shield Prince Siddhartha from these four realities of life. However, at age 29, Siddhartha, with his charioteer, went out of the protected palace grounds and, for the first time, encountered suffering, which he understood to be an inevitable part of life. He saw four sights: a man bent with old age, a person afflicted with sickness, a corpse, and a wandering ascetic. It was the fourth sight, that of a wandering ascetic, that filled Siddhartha with a sense of urgency to find out what lay at the root of human suffering.

Siddhartha left the luxury of the palace. He studied and lived an austere life in the forest with the foremost teachers and ascetics of his time. Yet, he found that their teachings and severe bodily austerities did not enable him to answer the question of suffering or provide insight into how to be released from it. Having experienced the life of self-indulgence in the palace and then the life of self-denial in the forest, he finally settled on a “middle way,” a balance between these two extremes. Accepting food from a village girl, he recovered his bodily strength and began a journey inward through the practice of meditation.