Shintō

Shintō

Shintō

Shintō Timeline

Shintō Timeline (text)

Ancient Origins of Shintō

Because Shintō is an indigenous cultural tradition emerging from ancient Japan, its origins cannot be clearly specified. However, there is archaeological evidence of belief in kami tracing back to the Yayoi period, 300 BCE - 300 CE. Though kami worship and shrine Shintō became systematized around the late 6th century CE, they were based on traditional forms that long preceded systematization. These ancient Shintō forms, rituals, and beliefs were not formalized or centralized, but were highly local, diverse, and community-based.

4 BCE The Ise Grand Shrine

The Ise Grand Shrine is one of the oldest, most important, and holiest sites in Shintō and Japanese history, and was first established in 4 BCE. It is located in Ise, Mie Prefecture of Japan, and is dedicated to the sun goddess Amaterasu.

3 BCE The Tsubaki Grand Shrine

The Tsubaki Grand Shrine, a Shintō shrine in Suzuka, Mie Prefecture, Japan was founded in 3 BCE. It is one of the oldest shrines in Japan, and the principal shrine of the deity Sarutahiko-no-Ōkami.

Ca. 456-459 CE Kami Rituals in Clan Communities

Clans with specializations that relate to kami ritual first appear. Many members of clan communities practiced sacred dancing, divination, and spirit possession.

6th century CE Buddhism and Shintō Meet

At the latter part of the Kofun period (300-538 CE), Buddhism entered Japan from Korea and began to interact with Shintō. Buddhism greatly influenced Shintō, and they syncretized in significant ways -- for example, kami were integrated into Buddhist cosmology. The introduction of Buddhism to Japan in the 6th century also led to the development of the term “Shintō” as a way to refer to the particular practices associated with the kami.

645-710 CE The Hakuhō Period

During the Hakuhō period, Shintō was established as the imperial faith of Japan, ending the previous predominance of clan Shintō. As the notion emerged that the Emperor and court had religious obligations, state leaders began to carry out court rites ensuring that kami would protect Japan. The Ise shrine became the main imperial shrine.

Because of the increasing influence of mainland Asian thought in the late 7th century CE, Japanese religion and laws began to be codified. One example of this is the Taiho Code (701 CE), or Ritsuryō, which codified Shintō rituals and required registration of all priests, monks, nuns, and temples.

8th Century CE Kojiki and Nihon Shoki

The Kojiki (712 CE) and Nihon Shoki (720 CE), the oldest classical Japanese texts and among the earliest written sources on kami worship, were written in the early Nara period (710-749 CE). These texts are compilations of Japanese mythology that comprise the basis of Shintō. They were intended to integrate Taoist, Confucian, and Buddhist themes into Shintō and to bolster the Imperial house. Throughout this same period, Shintō and Buddhism became deeply intertwined in Japanese culture and society.

759 CE The Manyoshu

The Manyoshu or Collection of 10,000 Leaves was written in 759. It is a classic of Japanese poetry and an important source in the Shintō tradition.

845 CE - 903 CE The Life of Tenjin

Sugawara no Michizane, also known as Kan Shōjō or Kanke, was a scholar, court official, and poet who lived from 845-903 CE. Today, he is known as Tenjin and revered as a deity of learning in Shintō.

1168 CE Rebuilding of the Itsukushima Shrine

The Itsukushima Shrine is one of the most iconic Shintō sites in Japan, and is said to have been first established in 593 CE under Empress Suiko. In 1168 CE, Taira no Kiyomori, a military leader, rebuilt the shrine in a new architectural style that is its present form.

1275 CE Imperial Court Elevates Kami

The imperial court elevates all kami by one rank in honor of their success in warding off Mongol invasion.

17th-18th centuries CE Shintō in the Early Modern Period

Throughout the early modern period, Japanese civil religion was characterized by heavy Confucian influences, but popular religion remained a blend of Shintō and Buddhist practices and beliefs. Shintō began to develop a stronger intellectual tradition during this time.

1838 CE Founding of Tenrikyo

Tenrikyo, or “Religion of Heavenly Truth,” is a Japanese new religion with a strong Shintō orientation. It was founded in 1838 by female religious leader Nakayama Miki (1798-1887) as a result of a series of revelations she received.

1859 CE Founding of Konkokyo

Bunji Kawate (1814-1883), also known as Konko Daijin, founded the Japanese new religion Konkokyo in 1859 CE. Konkokyo centers on belief in and worship of a single all-sustaining spirit that flows through all things. Later after Konko Daijin’s death, Konkokyo was classified as one of the thirteen sects of Shintō.

1868 CE State Shintō

State Shintō emerged in 1868 when the Meiji monarchy established Shintō as the foundation of the modern state of Japan. This involved largely unsuccessful attempts to disentangle “real” Shintō from other influences, especially Buddhism, and to undermine the prominence of Buddhism in Japan. Shrines were brought under administrative control of the Department of Divinities (Jingikan).

A few years later, the Meiji government designated 13 new religious movements as forms of “Sect Shintō.” The initial Meiji practice of sponsoring shrines declined, but the state continued to use Shintō mythologies in its nationalism and in legitimizing the Emperor’s power. State Shintō was ultimately abandoned after World War II.

1946 CE Shintō after World War II

In the wake of the second World War, State Shintō was abandoned by the Japanese government. However, Shintō remained an integral part of Japanese life and society. In 1946, many Japanese shrines organized themselves into the Association of Shintō Shrines as a way to foster coordination and cooperation. By the late 1990s, approximately 80% of shrines in Japan belonged to the Association.

1969 CE Shintō Groups in International Interfaith Organizations

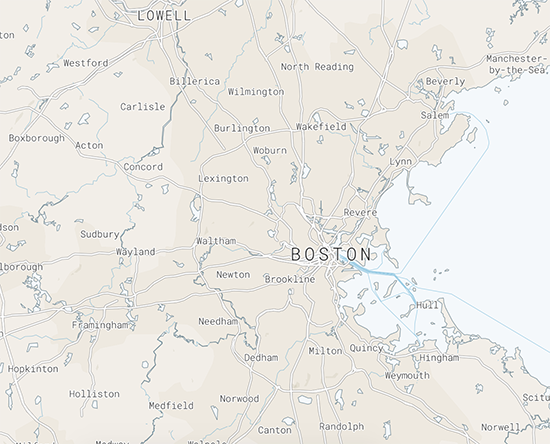

As early as the 1930s, there was frequent contact between Shintō priests at the Tsubaki Grand Shrine and Unitarians, both Japanese and American. This relationship later led to Japanese Shintō groups joining the International Association for Religious Freedom and attending the 1969 IARF Congress in Boston, MA.

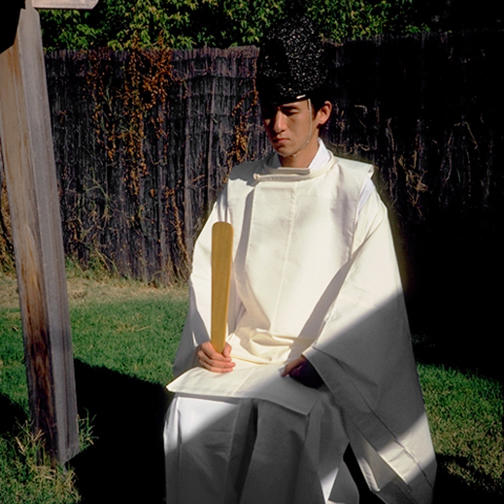

1986 CE The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America

The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America was built in 1986 in Stockton, CA, and in 2001 moved to its current location in Granite Falls, Washington state. It was the first Shintō shrine built in the mainland United States after World War II. Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is a branch of Tsubaki Ōkami Yashiro, one of the oldest shrines in Japan. The current Guji, or Head Priest, is Rev. Koichi Barrish, who is the first American priest in Shintō history.

Shintō Today

Today, aspects of Shintō have been integrated with various traditions and new religious movements in Japan. Shintō is currently the most popular religion in Japan, with around 80,000 public Shintō shrines existing in Japan today. Shintō is also practiced in many different parts of the world, alongside other traditions and religious practices. In the United States, though there are a relatively small number of practitioners, there are several Shintō shrines.

Explore Shintō in Greater Boston

Though there are significant Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Korean immigrant communities in Greater Boston, East Asian traditions such as Confucianism, Daoism, and Shintō are difficult to survey as there are very few religious centers. These traditions are deeply imbedded in the unique history, geography, and culture of their native countries and are often practiced in forms that are not limited to institutional or communal settings.