In the ancient Near East, the Jewish theology of one singular, universal God represented a synthesis of existing beliefs and an influential innovation in the history of the world’s religions.

In the ancient Near East, the Jewish theology of one singular, universal God represented a synthesis of existing beliefs and an influential innovation in the history of the world’s religions.

The vision of a universal, singular God is arguably one of the greatest religious innovations of the Jewish tradition among the world’s historic religious systems. Between 1500 and 500 BCE, the Israelite people of the ancient Near East began to articulate a radical new understanding of divinity. The ancient Hebrews were most likely polytheistic, believing in numerous deities representing different forces of nature and serving various tribes and nations. Eventually, however, early Hebrew visionaries and prophets began to speak boldly of one God as the creator of all existence, a view we have come to call monotheism. Expressing the multivalent nature of divinity as well as insisting upon the oneness of God, early Hebrew authors gave God names such as Elohim (gods), Adonai (my lord), and the unpronounceable YHWH, from the same root as the verb “to be,” also the etymological source of the name “Jehovah.”

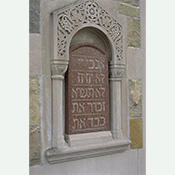

Through the visions and the voices of prophets, the God the Hebrews encountered was all-powerful and benevolent, merciful and just. Rejecting the anthropomorphic tendency of the time, the Hebrews did not represent God in any human form or earthly likeness, but as a universal God, engaged in a lasting relationship with humankind through the instruments of revelation, Torah, and a covenantal people, Israel. This emerging understanding of God would have profound implications for the history of Western religion.

Geographical context, of course, was essential to the development of ancient Israelite monotheism. Living in the land of Canaan, situated midway between the civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt at the heart of the Fertile Crescent, the ancient Hebrews were exposed to the religious cultures of multiple world powers. While Mesopotamian deities, represented in the form of images, were numerous, Mesopotamian society was ordered by a permanent set of laws—the Code of Hammurabi—and not subject to the capriciousness of their many gods. Meanwhile, Egyptian religion posited an unchanging set of nature deities represented on earth by a divine ruler, the Pharaoh. The Hebrews, originating in Mesopotamia and enslaved for generations in Egypt, adopted elements of both world views. They rejected the idol worship of Mesopotamian religion while preserving the rational and just organization of its society, and rejected the human deification of the Egyptian Pharaoh while preserving the singularity of his rule: God alone is sovereign. Through negotiating the polytheism and idolatry of religious cultures at the time, the Hebrew concept of God drew in large part from the Israelites’ Near Eastern neighbors.

Despite these continuities, there was something quite new in the Hebrews’ understanding of God. Unlike the Mesopotamians or the Egyptians, the ancient Hebrews affirmed that their laws came directly from God. God’s gift of the Torah on Mount Sinai became pivotal in the Hebrew people’s self-understanding. God was not an abstract concept or principle, but actively involved in history through revelation and covenant. Throughout Jewish history, the common thread has been God’s relationship with humanity. Every Jewish theological concept of God has implications for the nature of human existence: God’s creation of the universe, including the possibilities of good and evil, implies the existence of human free will and leads ultimately to a belief in human freedom and dignity. At the same time, God’s covenant with the Jewish people and involvement in human history implies that individuals and societies exist for a reason, unfolding along a known plan.

These themes, initially developed through oral literature, were soon compiled into the written record of the Hebrew Scriptures; in such fashion did the ancient Hebrews bequeath this novel theology to the world. Jews today continue to pride themselves on the fact that the ethical monotheism of Judaism is the basic building block of Western religion. The idea of one God unites broad human communities historically, religiously, and culturally to the present day.