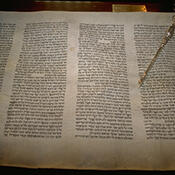

The Jewish commentaries and interpretations of the Bible, ranging from legal codes to rabbinic dialogues, from philosophical inquiry to folklore, collectively form the Talmud. The earliest commentary is called the Mishnah, while the later commentary on and elaboration of the Mishnah is called the Gemara, taken together these two commentaries make up the Talmud. Talmudic Midrash, another genre of rabbinic writing, also includes stories, philosophical explications, and historical writing.

The Jewish commentaries and interpretations of the Bible, ranging from legal codes to rabbinic dialogues, from philosophical inquiry to folklore, collectively form the Talmud. The earliest commentary is called the Mishnah, while the later commentary on and elaboration of the Mishnah is called the Gemara, taken together these two commentaries make up the Talmud. Talmudic Midrash, another genre of rabbinic writing, also includes stories, philosophical explications, and historical writing.

Traditionally, Judaism today is conceived as a timeless and ongoing conversation between the Jews and God, based on centuries of religious development and voluminous writings. These legal and interpretative texts, arguably the sum total of the discussion, argumentation, and writings of rabbis through the ages, is commonly called rabbinic literature. Rabbinic literature is a religious textual compendium developed over the history of the Jewish people, particularly in the Second Temple period and afterward.

The rabbis designated their literature the Oral Torah, as opposed to the finalized canon of the Written Torah. While the Torah refers mainly to the five books of Moses, it also refers more widely to all of Jewish sacred literature. To ensure the durability and relevance of the Biblical tradition, rabbis drew a distinction between the written Torah dictated by God to Moses on Mount Sinai and the unwritten Torah dictated by God to Moses verbally. According to rabbinic tradition, this second tradition was passed down orally, eventually developed in writing by the rabbis of the 3rd century CE in Palestine and becoming known as the Mishnah.

Thought to be modeled on the curriculum of the post-temple yeshiva (a school for rabbinic study), the Mishnah is the basic code of post-biblical Jewish law. The text’s many sections concern the whole spectrum of individual and community life—laws of agriculture, prayers and benedictions, the observances of Sabbath and holidays, women and family law, property, inheritance, and criminal law, sacred objects and ritual associated with the temple, and ritual purity and impurity.

During the 3rd to 6th centuries, the rabbis of the yeshivas in Palestine and Babylonia continued to study and debate the rulings of the Mishnah. Their deeply analytical discussions in the Aramaic vernacular of the day were preserved in the Gemara (an elaboration of, or commentary on, the Mishnah). As a pair, the Mishnah and the Gemara form the Talmud, of which there are two extant versions. The Palestinian Talmud was finished in the early 5th century; the lengthier and more authoritative Babylonian Talmud was completed by the beginning of the 6th century.

One important distinction between the Mishnah and the Gemara is their context of reference. As a relatively specific text, the legal code of the Mishnah necessarily acknowledged the destruction of the temple in 70 CE, but primarily addressed Jewish corporate existence within the holy land of Israel. The Gemara, on the other hand, presupposed the reality of exile from Israel and addressed itself more generally to Jewish life in Diaspora (galut). One of the underlying themes of the Talmud is the accommodation of Judaism to the minority status of Diaspora Jewry. Much of its legal discussion, therefore, is theoretical and abstract rather than literal and applied, including legislative debate on issues such as criminal law, torts or damages, civil rights and administration, and family law. The legacy of the Talmud is important to note: because Jewish civil law was often superseded in Diaspora by the rule of the state, the forms of critical reading and argumentation of the Talmud today serves a more pedagogical purpose. The commentaries are used to sharpen the reasoning powers of Jewish scholars by means of Talmudic logic.

In addition to the Mishnah and the Gemara, the Talmud contains material that could better be called folklore, history, ethics, and philosophy. This is collectively called aggadah (or haggadah), constituting approximately one-third of the Babylonian Talmud. The rabbis also wrote complete works of biblical interpretation called Midrash. The whole of the Talmud (the Mishnah and the Gemara, as well as all of the Talmud’s later appendices and elaborations) forms the bulk of rabbinic literature, or “Oral Torah.” This living tradition of scripture guaranteed the permanent relevance of the Torah and preserved the importance of the rabbi’s role as scholar and interpreter of a living tradition for each generation. Rabbinic commentary on both the Torah and the Talmud continued throughout the centuries, and came to be incorporated into the study of the text. Perhaps the greatest individual commentator was Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac of Troyes, France, known by his acronym, Rashi. Rashi was the first commentator to systematically write on all of the Torah and nearly all of the Talmud. His commentary has been so influential for subsequent generations of Jews that it has been printed often alongside the text of the Torah and Talmud. Rashi’s 11th century commentaries are used in Jewish study to this day.

Through the centuries, the major discipline within the rabbinic literary tradition has remained Jewish law, halakhah. Following the completion of the Talmud, far-flung Jewish communities often depended upon leading rabbinic authorities elsewhere in the world to render legal opinions. These legal queries and rabbinic replies constitute the body of legal literature called Responsa, which continues to be produced in the present day. Jewish life in the Diaspora also required a more systematic treatment of religious practice, and in the later middle ages two major works codifying Jewish law and practice were produced: Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah (c. 1178) and Joseph Caro’s Shulchan Aruch (1564). Both works continue to be studied today by traditionally observant Jews. While an abbreviated version of the Shulchan Aruch is more accessible, it has by no means replaced the unabridged version.

Perhaps the most important legacy of the rabbis is the tradition of lifelong study. As the rabbis intended, the study of Torah and the Talmud are ongoing enterprises. Through study, debate, discussion, and appropriation by each generation, Judaism is indeed a living tradition.